Sensors detect disease markers in breath

- News

- 2.2K

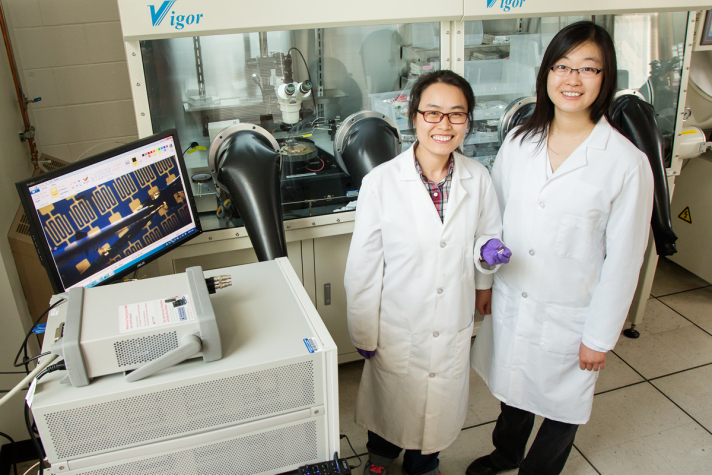

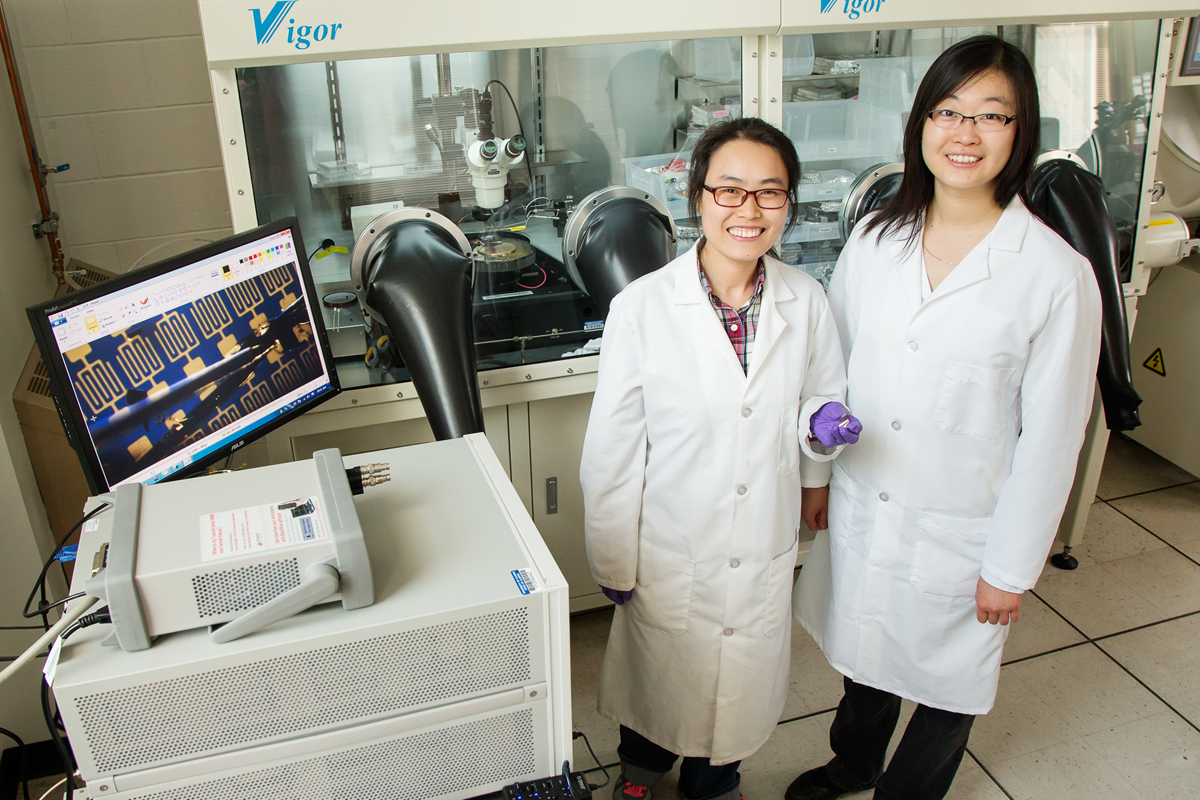

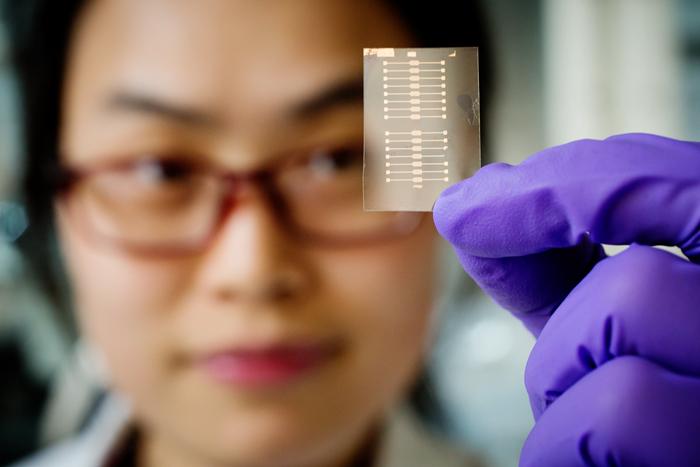

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — A small, thin square of an organic plastic that can detect disease markers in breath or toxins in a building’s air could soon be the basis of portable, disposable sensor devices. By riddling the thin plastic films with pores, University of Illinois researchers made the devices sensitive enough to detect at levels that are far too low to smell, yet are important to human health.

In a new study in the journal Advanced Functional Materials, professor Ying Diao’s research group demonstrated a device that monitors ammonia in the breath, a sign of kidney failure.

“In the clinical setting, physicians use bulky instruments, basically the size of a big table, to detect and analyze these compounds. We want to hand out a cheap sensor chip to patients so they can use it and throw it away,” said Diao, a professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Illinois.

Other researchers have tried using organic semiconductors for gas sensing, but the materials were not sensitive enough to detect trace levels of disease markers in the breath. Diao’s group realized that the reactive sites were not on the surface of the plastic film, but buried inside it.

“We developed this method to directly print tiny pores into the device itself so we can expose these highly reactive sites,” Diao said. “By doing so, we increased the reactivity by ten times and can sense down to one part per billion.”

For their first device demonstration, the researchers focused on ammonia as a marker for kidney failure. Monitoring the change in ammonia concentration could give a patient an early warning sign to call their doctor for a kidney function test, Diao said.

The material they chose is highly reactive to ammonia but not to other compounds in breath, Diao said. But by changing the composition of the sensor, they could create devices that are tuned to other compounds. For example, the researchers have created an ultrasensitive environmental monitor for formaldehyde, a common indoor pollutant in new or refurbished buildings.

The group is working to make sensors with multiple functions to get a more complete picture of a patient’s health.

“We would like to be able to detect multiple compounds at once, like a chemical fingerprint,” Diao said. “It’s useful because, in disease conditions, multiple markers will usually change concentration at once. By mapping out the chemical fingerprints and how they change, we can more accurately point to signs of potential health issues.”